I Spent 50+ Hours Analyzing the First Harry Potter Book

Analysis of "Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone" by J.K. Rowling

The Harry Potter phenomenon has enchanted minds of all ages, expanding into an empire that encompasses films, video games, merchandise, and theme parks.

But it all started with a book…

Since the publication of J.K. Rowling's debut novel, Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, in 1997, the world has been enthralled by the magical universe she created.

I spent 50+ hours analyzing Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone to gain a better understanding of how J.K. Rowling captivated readers with this first story.

How do you compel readers to keep turning the page?

The lessons I learned from over fifty hours of analysis transformed from my writing style and were directly applied to my first novel.

I’m here to share what I’ve learned so you can improve your own writing.

* * * Spoilers for all seven Harry Potter novels below * * *

First, here’s my book after 50+ hours:

Follow Along:

Throughout this analysis, I will reference numerous examples from The Sorcerer’s Stone alongside page numbers. Here’s a link if you want to follow along.

The Focus of My Analysis:

A successful novelist must be able to hold a reader’s attention across hundreds of pages. This is a task much easier said than done because, let’s face it, books often reach lulls and are abandoned by readers midway. J.K. Rowling managed to hold the attention of both children AND adults across this Harry Potter first book and the entire seven book series.

Readability is the most crucial factor in writing a novel.

I’d argue that readability is more relevant than ever in today’s digital world. A book must be extraordinarily compelling in order to win the attention battle with our phones. Companies have spent billions of dollars engineering apps that mesmerize us to a point where we lose track of time altogether.

You have to grab the reader as quickly as possible (ideally the first page) and propel them through the story you’ve created. Even if you’ve crafted a brilliant story, you most likely won’t get a chance to tell it if you’re not able to hold a reader’s attention. Harry Potter stories are mysteries, but the techniques used to improve readability can be applied to all genres.

Disclaimer: This is is LONG post.

But is it is full of VALUE — there are so many techniques from The Sorcerer’s Stone that can transform how we write out novels. J.K. Rowling knew what she was doing.

Here’s the Full Outline:

1. Create Questions

2. Make Things Clear

3. Chapter Design

4. Raise the Stakes

5. Use Inserts

6. Capitalize on Time Jumps

1. Create Questions

" The most powerful person in the world is the storyteller. The storyteller sets the vision, values, and agenda of an entire generation that is to come." - Steve Jobs

Your job as a storyteller is to create questions in a reader’s mind and make them want to keep reading so they can find out the answer. The more questions, the better, and there is a range of time frames that the questions can span.

Questions answered within the book

Questions answered within the chapter

Questions answered within the series

There is one massive caveat to this technique: All questions must be answered!

The reader puts a tremendous amount of faith in you as a storyteller to give them a meaningful emotional experience. They give you their time and money and in return expect a cohesive story within no loose ends left untied. It is not fair or smart to create questions as an end in itself. Don’t play any tricks by creating questions that go unanswered, all you’ll do is anger the reader. If the reader loses faith in you as the storyteller, you’re doomed. Every setup must have a payoff.

Questions can be created in a reader’s mind by withholding information, or even writing the question itself through a character’s internal thoughts.

Dozens of questions spring to mind beginning from the very first chapter and throughout the entirety of Harry Potter and the Sorcerer’s Stone. These questions span across the three time frames we have established: book, chapter, and series.

Questions within the book

It’s not enough to make readers WANT to finish your book.

Make it so readers NEED to finish your book.

Do this by creating question that will be answered in the final pages. If you do this successfully, your readers will be scrambling to find out what happens at the end.

In the first Harry Potter, the questions answered within the book are mostly tied to the mystery surrounding the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Here are some examples:

What did Hagrid take from Gringott’s? (P. 76)

What have the Centaurs read in the movement of the planets? (P. 257)

Who left the invisibility cloak for Harry? (P. 261)

All of the questions in the above examples are answered by the end of the book. The Harry Potter series makes a point of wrapping up loose ends, with each usually ending with a question-and-answer segment between Harry and Dumbledore.

Answers are necessary to ensure that the reader has a meaningful emotional experience. If your ending isn’t satisfying, you need to fix it. Don’t cheat. If a reader is willing to give you their prolonged attention, make sure you wow them.

Questions within the chapter

If questions answered within the book keep the reader anticipating the final pages, how do you hold interest along the journey?

This is where creating questions that are answered within the chapter are necessary. These questions could be answered at the end of the chapter, or even immediately after they are presented.

Create as many questions as possible at all times.

Even the smallest delays in information can have an impact.

For example, if your character hatches a plan, don’t tell the reader what it is. Have them on the edge of their seat as they try to keep up with the action. Remember when Harry wanted to outmaneuver the Dursleys so he could look at the mysterious letters arriving at Privet Drive?

Harry walked round and round his new room. Someone knew he had moved out of his cupboard and they seemed to know he hadn’t received his first letter. Surely that means they’d try again? And this time he’d make sure they didn’t fail. He had a plan. (P. 39)

There’s then a chapter break and the next section opens with Harry sneaking out of his room. As the reader, we know Harry is motivated to achieve a particular goal, but we are eagerly waiting to see how he goes about reaching it. Could Rowling have written that Harry was going to wake up early the next morning to be the first at the mail slot? Sure. But that might not have encouraged us to keep reading past the chapter break and onto the next section.

A technique that seems so small works to hold the reader’s attention and keep the pages turning.

Here are some more examples to inspire use for your own writing:

It was lucky that Harry had tea with Hagrid to look forward to, because the Potions lesson turned out to be the worst thing that happened to him so far. (P.136)

What bad thing happens during potions?

Then a sudden movement ahead of them made them almost drop the crate. (P. 240)

What is ahead of them?

“Right then,” said Hagrid, “now, listen, carefully, ‘cause it’s dangerous what we’re gonna do tonight, an’ I don’ want no one takin’ risks. Follow me over here a moment.” (P. 250)

What do they have to do in the Forbidden Forest?

“Did that sound like hooves to you? Nah, if yeh ask me, that was what’s bin killin’ the unicorns — never heard anythin’ like it before?” (P. 254)

What mysterious creature is killing the unicorns?

“But the night’s surprises weren’t over.” (P. 261)

What surprise will happen next?

“Lucky!” shrieked Hermione. “Look at you both!” (P. 277)

What is wrong with Harry and Ron?

“There’s light ahead — I can see something moving.” (P. 279)

What is awaiting them in the next chamber?

The goal is to keep the read on the edge of their seat, wanting to find out what happens next. You can create questions by making the slightest changes to the structure of a chapter. Rowling even uses a technique where she presents dialogue before revealing who is actually speaking.

“Do you mean,” Harry croaked, “that was Vol—”

“Harry! Harry, are you all right?”

Hermione was running toward them down the path, Hagrid puffing along behind her. (P. 259)

Here’s another example of “dialogue before appearance”:

“We’ll just have to—” Harry began, but a voice suddenly rang across the hall.

“What are you three doing inside?”

It was Professor McGonagall, carrying a large pile of books. (P. 267)

And here’s an example of the “description before identification” technique:

Something bright white was gleaming on the ground. They inched closer.

It was the unicorn all right, and it was dead. (P. 255)

Get creative with how you structure your writing so that readers want to tear through each chapter. Additionally, a question should be presented at the very end of each chapter that makes the reader want to turn the page (more on that later).

Questions within the series

I’ve put this section last because you may not be writing a series. Assuming you are, you’ll want to make sure you establish questions complex enough to be examined throughout all planned installments.

Central questions arise from the opening pages of The Sorcerer’s Stone that are answered over the course of the seven book series. These questions relate to the murder of Harry’s parents, Lily and James Potter.

Why did Voldemort want to kill Harry?

How did Harry survive?

Who is Voldemort?

These questions are the focus of the many pages of later stories.

All are answered.

I believe this central mystery is why the Harry Potter story is so captivating in the first place. The series is not about the individual mysteries of a Chamber of Secrets or Half-Blood Prince, it’s about reading to fully understand the events described in the opening pages of the very first chapter of the first book. The Sorcerer’s Stone even concludes with another tease to the mystery, with Harry asking, “But why would he want to kill me in the first place?” Dumbledore answers by hinting at reasons that we will not fully understand until the final pages of the seventh book:

“Alas, the first thing you ask me, I cannot tell you. Not today. Not now. You will know, one day… put it from your mind for now, Harry. When you are older... I know you hate to hear this… when you are ready, you will know.” (P. 299)

It’s almost like Dumbledore is speaking to the reader directly and saying to be patient, the answers you’re looking for are to come.

Rowling was able to hold interest throughout the following adventures and bring a satisfying conclusion with no loose ends.

2. Make Things Clear

It is essential for writers to avoid causing confusion or creating interruptions in the flow of the narrative. A reader should never encounter moments of puzzlement that lead them to pause or, even worse, go back and reread previous pages or chapters.

The goal is to maintain a steady pace that keeps readers completely absorbed until the very end. Achieving clarity in our writing is the key to ensuring that readers never feel lost or disoriented.

J.K. Rowling demonstrates a mastery of providing clarity in her storytelling. Throughout her works, Rowling skillfully reiterates crucial information at strategic points to keep readers up-to-speed on essential plot developments and character nuances. By strategically reintroducing key details, readers are continuously reminded of the necessary information to advance the story smoothly.

The Mystery

The mystery surrounding the Sorcerer’s Stone involves a variety of elements that risk confusing readers as they experience their first encounter with the Wizarding World.

J.K. Rowling expertly weaves together multiple elements and red herrings to add layers of complexity to the mystery. Yet, even amid the twists and turns, Rowling ensures that readers are never lost in the labyrinth of clues and revelations. The story primarily unfolds through the perspective of Harry Potter, and the seamless blend of narrative and dialogue allows for relevant information to be effectively conveyed.

An excellent example of this can be found in the closing moments of chapter thirteen, where essential information is conveyed through a well-crafted dialogue exchange:

“So we were right, it is the Sorcerer’s Stone, and Snape’s trying to force Quirrell to help him get it. He asked if he knew how to get past Fluffy — and he said something about Quirrell’s ‘hocus-pocus’ — I reckon there are other things guarding the stone apart from Fluffy, loads of enchantments, probably, and Quirrell would have done some anti-Dark Arts spell that Snape needs to break through—” (P. 227)

Rowling will even remind readers of key details by giving us Harry’s direct perspective:

There was no doubt about it, Hagrid definitely didn’t meet Harry’s eyes this time. He grunted and offered him another rock cake. Harry read the story again. The vault that was searched had in fact been emptied earlier that same day. Hagrid had emptied vault seven hundred and thirteen, if you could call it emptying, taking out that grubby little package. Had that been what the thieves were looking for? (P. 142)

We are always kept aware of the essential information as the story propels forward and the mystery unravels.

Character Relationships:

In a story that involves questioning the motivations of side characters, it is important for the reader to know how the protagonist feels about others in the cast.

Hermione is largely regarded as a nuisance for the beginning portion of the novel. It’s not until the incident with the troll in chapter 10: Halloween that Harry and Ron become friends with her. This is an important shift in dynamics for the rest of the story and Rowling makes the change extremely clear:

But from that moment on, Hermione Granger became their friend. There are some things you can’t share without ending up liking each other, and knowing out a twelve-foot mountain troll is one of them. (P. 179)

Making character relationships clear is essential when dealing with red herring characters. Despite Quirrell being the actual villain of the story that is attempting to steal the Sorcerer’s Stone, we are led to suspect Snape. Rowling makes it clear that Harry and his friends do not suspect Quirrell:

Whenever Harry passed Quirrell these days he gave him an encouraging sort of smile, and Ron had started telling people off for laughing at Quirrell’s stutter. (P. 228)

Making the reader aware of their positive feelings toward Quirrell makes the reveal in the final act incredibly shocking.

3. Chapter Design

You should put a great amount of focus on designing suitable chapters when plotting your novel. Each chapters should be a mini-story in itself that holds the readers attention.

Chapter Length:

Chapters should be in the same page range across your novel. There can certainly be some chapters longer than others — like during act climaxes — but for the most part they should be around the same number of pages.

A chapter should never outstay its welcome. Some others, like Dan Brown of The Da Vinci Code fame, employ of the use of micro chapters to make readers keep turning the page. Focus on finding the “mini-stories” in your narrative that can become our chapters. You don’t have to reach micro-chapter levels, but if you’re chapter can be split up, I’d say do it. Keep the pages turning.

As shown in the graph below, Rowling holds a nice page range in The Sorcerer’s Stone:

You can see peaks peaks around notable points in the story when the excitement ramps up.

In chapter 5 & 6 — “Diagon Alley” and “The Journey from Platform Nine and Three- Quarters — we first travel to key locations of the Wizarding World.

Chapters 15, 16, & 17 are our final act where we get our answers surrounding the mystery of the Sorcerer’s Stone.

Note that there’s no single chapter that shoots too high above the others.

How to End Chapters:

When locating the mini-stories of the larger narrative that will become your chapters, make sure you can end in a way that makes the reader want (or better, NEED) to turn the page.

In part 1a) of this analysis we discussed creating questions in the mind of readers.

Apply the lessons learned and create a question at the end of each chapter.

Here’s an example from the end of chapter sixteen, “Through the Trapdoor”:

It was indeed as though ice was flooding his body. He put the bottle down and walked forward; he braced himself, saw the black flames licking his body, but couldn’t feel them — for a moment he could see nothing but dark dire — then he was on the other side, in the last chamber.

There was already someone there — but it wasn’t Snape. It wasn’t even Voldemort.

After reading that, you’re left screaming: WHO IS THERE???

More than anything in the world, you’re left wanting to turn the page and read the answer.

But not every point in the story will have dramatic moments like the previous example. What if you can’t end your chapter by withholding a reveal?

Rowling ends the less dramatic chapter eight, “The Potions Master,” by summarizing the clues at this point in the mystery surrounding the main narrative.

As Harry and Ron walked back to the castle for dinner, their pockets weighed down with rock cakes they’d been too polite to refuse, Harry thought that none of the lessons he’d had so far had given him as much to think about as tea with Hagrid. Had Hagrid collected that package just in time? Where was it now? And did Hagrid know something about Snape that he didn’t want to tell Harry? (P. 142)

With questions even directly written, the reader is left wondering about the mystery and thereby inclined to keep reading for the answers.

4. Raise the Stakes

The higher the stakes in your novel, the more a reader will want to find out how things end for your characters.

There’s a point in The Sorcerer’s Stone where the stakes change dramatically. For most of the novel, we are teased with clues surrounding the mystery of the Sorcerer’s Stone and who may be trying to steal it. This mystery certainly holds our attention, but Rowling takes things further.

Before actually going after the Sorcerer’s stone in the final events of the book, the stakes are raised for our main characters that makes finding out what happens at the end that much more desirable.

The school consequences of Harry, Ron, and Hermione’s potential actions are clearly outlined in two ways within the same page (P. 269).

They’ll be expelled, as noted by Snape:

“Be warned Potter, — any more nighttime wanderings and I will personally make sure you are expelled. Good day to you.” (P. 269)

And they’ll lose house points for all of Gryffindor, as noted by McGonagall:

“I suppose you think you’re harder to get past than a pack of enchantments! she stormed. “Enough of this nonsense! If I hear you’ve come anywhere near here again, I’ll take another fifty points from Gryffindor! Yes, Weasley, from my own House!” (P. 269)

These two consequences definitely ratchet up the stakes at the end of the story, but Rowling takes things even further.

She makes the stakes life or death:

“SO WHAT? Harry shouted. “Don’t you understand? If Snape gets hold of the Stone, Voldemort’s coming back! Haven’t you heard what it was like when he was trying to take over? There won’t be any Hogwarts to get expelled from! He’ll flatten it, or turn it into a school for the Dark Arts! Losing points doesn’t matter anymore, can’t you see? D’you think he’ll leave you and your families alone if Gryffindor wins the House Cup? If I get caught before I can get to the Stone, well, I’ll have to go back to the Dursleys and wait for Voldemort to find me there, it’s only dying a bit later than I would have, because I’m never going over to the Dark Side! I’m going through that trapdoor tonight and nothing you two say is going to stop me! Voldemort killed my parents, remember?”

In an intense dialogue exchange, Harry clearly outline the stark consequences of Voldemort’s potential return. With this, the story changes from a fun mystery in a magical castle to something darker. You begin to fear for the main characters and what could possibly happen if they fail. This raising of the stakes propels the reader forward through the final pages.

5. Use Inserts

Inserts, also known as intertextual elements, are additional textual components, such as letters, newspapers, or diary entries, seamlessly integrated into the main narrative.

Inserts are a great tool to use in your novel for immersing your readers in the world of your story. We get to experience reading information alongside a character. In a more general sense, they are also great for breaking reader fatigue.

Here are some examples from The Sorcerer’s Stone.

Harry’s Hogwarts Acceptance Letter (P. 51):

As we read through this insert, we experience getting accepted into Hogwarts alongside Harry. Note the added detail of Professor McGonagall’s signature.

Hogwarts School Supplies List (P. 66):

The supplies list is an amazing piece of worldbuilding. We pick up small details that help to solidly the Wizarding World in our minds. Did you notice Fantastic Beast and Where to Find Them listed? This small detail would become the basis of three Harry Potter spinoff films.

Book Page about Nicolas Flamel and the Sorcerer’s Stone (P. 220):

Instead of having Hermione recite the relevant information as she’s reading, we get to read alongside our characters. This is much more interactive and a change-up from how previous information has been conveyed.

The Bottle Puzzle (P. 285):

By reading the actual text ourselves, we get to solve the puzzle along with the characters. The change in format allows a longer puzzle, too. The information couldn’t be converyed as effectively through extended dialogue.

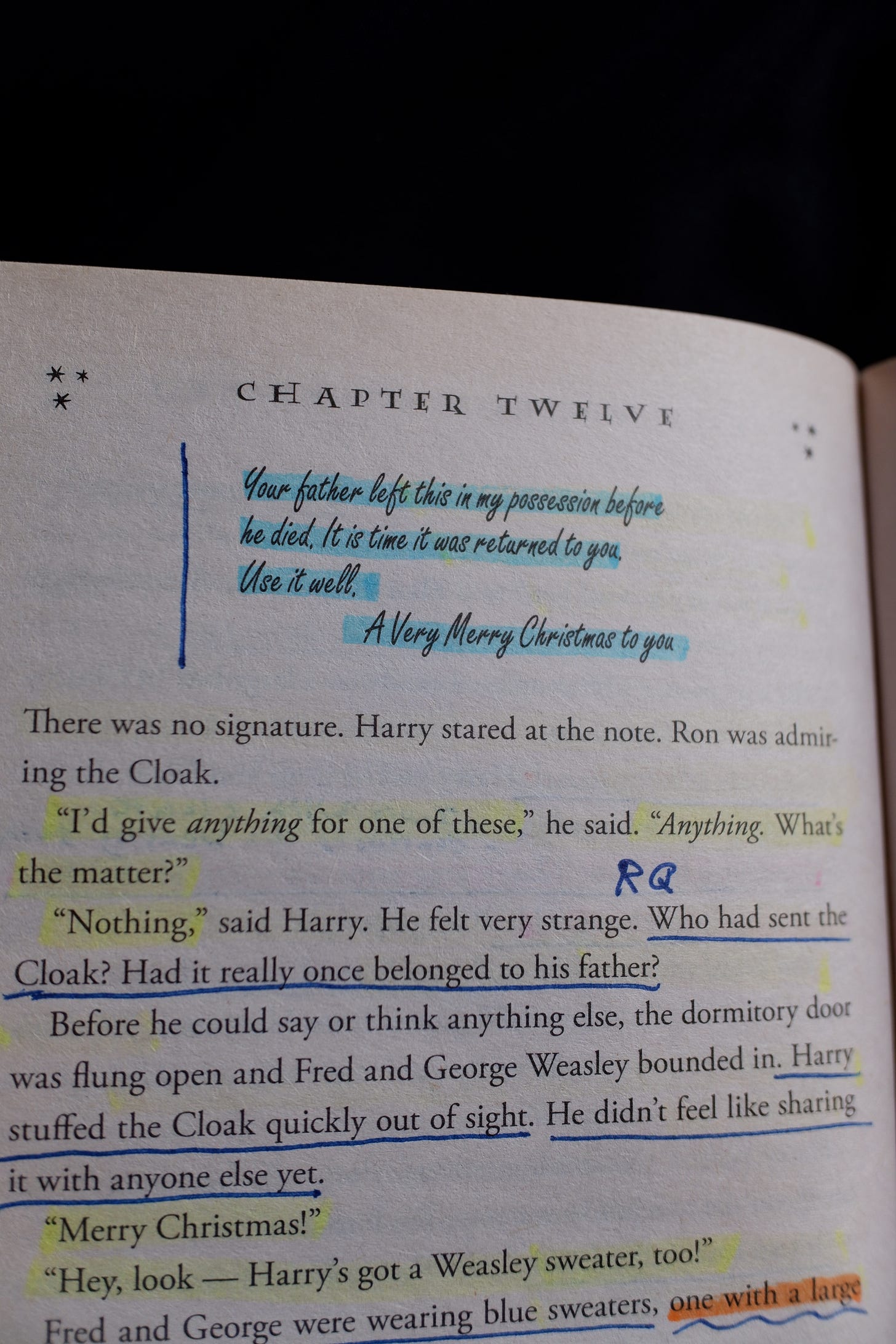

The Letter Alongside the Invisibility Cloak (P. 202):

There’s a clue woven into this insert: with the identity of the letter’s author unknown, we can theorize as to who’s behind the loopy handwriting. This makes the reader think back to the other inserts, and whether the handwriting has been used previously.

The clever integration of inserts in The Sorcerer’s Stone allows readers to be spellbound by the wonders of the Wizard World, forging a connection that has endured for generations.

Use inserts in your own writing to further immerse your readers.

6. Capitalize on Time Jumps

Here’s a key way to make your readers keep turning the pages:

Create a world that your readers never want to leave.

J.K. Rowling is the master of this, with The Sorcerer’s Stone introducing us to her Wizarding World.

She does this through a variety of ways, but during my 50+ hour analysis I noticed an underutilized technique that could be applied to any genre.

Whenever there’s a time jump in The Sorcerer’s Stone — it could be weeks or months — Rowling uses the opportunity to pack in details about the world. She never misses an opportunity to flesh out characters or the environment.

Let’s look at some examples.

Time Jump in Summer (P. 31):

The escape of the Brazilian boa constrictor earned Harry his longest-ever punishment. By the time he was allowed out of his cupboard again, the summer holidays had started and Dudley had already broken his new video camera, crashed his remote control airplane, and, first time out on his racing bike, knocked down old Mrs. Figg as she crossed Privet Drive on her crutches.

The mere mention of Mrs. Figg in this passage opens the scope of Privet Drive to more than just the Dursley family. We also get more insight into Dudley as a spoiled child through the broken objects listed.

Time Jump in Fall (P. 180):

"As they entered November, the weather turned very cold. The mountains around the school became icy gray and the lake like chilled steel. Every morning the ground was covered in frost. Hagrid could be seen from the upstairs windows defrosting broomsticks on the Quidditch field, bundles up in a long moleskin overcoat, rabbit fur gloves, and enormous beaverskin boots.”

Instead of only commenting on the change of weather, Rowling provides insight into Hogwarts life by mentioning Hagrid everyday duties.

Time Jump in Winter (P. 194):

Christmas was coming. One morning in mid-December, Hogwarts woke to find itself covered in several feet of snow. The lake froze solid and the Weasley twins were punished for bewitching several snowballs so that they followed Quirrell around, bounding off the back of his turban. The few owls that managed to battle their way through the stormy sky to deliver mail had to be nursed back to health by Hagrid before they could fly off again.

No one could wait for the holidays to start. While the Gryfindor common room and the Great Hall had roaring fires, the drafty corridors had become icy and a bitter wind rattled the windows in the classrooms. Worst of all were Professor Snape’s classes down in the dunfeons, where their breath rose in a mist before them and they kep as close as possible to their hot cauldrons.

This one is my favorite. Look at all the details she packs in — Fred & George, Quirrell, the owls, Hagrid, the common room, Potions class. Hogwarts feels like a real place.

Time Jump in Spring (P. 229)

Unfortunately, the teachers seemed to be thinking along the same lines as Hermione. They piled so much homework on them that the Easter holidays weren’t nearly as much fun as the Christmas ones. It was hard to relax with Hermione next to you reciting the twelve uses of dragon’s blood or practicing wand movements. Moaning and yawning, Harry and Ron spent most of their free time in the library with her trying to get through all their extra work.

Notice how Rowling adds specificity to the trio studying in the library — “reciting the twelve uses of dragon’s blood or practicing wand movements.”

Do you have any time jumps in your story?

Use the passage of time as an opportunity to pack in detail and create a world that your readers never want to leave.

Final Thoughts:

By diving deep into Harry Potter and the Sorcerer's Stone, we’ve unveiled the magic behind J.K. Rowling's storytelling brilliance.

As writers and storytellers, we can draw invaluable insights from Rowling's craft, learning how to captivate readers with our own stories.

Thanks for joining me in this analysis.

Know anyone who’d be interested in reading this analysis? 🤔

Thank you for compiling this analysis. I genuinely appreciated all the insights. J.K. Rowling is undoubtedly a master of her craft.